Behind the Scenes at Citizenship Classes

What happens in citizenship classes?

BIIN’s citizenship classes are offered in both English and Spanish, on a ten-week cycle. Since fall 2020, all classes have been meeting via Zoom. A typical class begins with a short lecture by the designated instructor, to introduce the concepts, governmental principles or historical events whose significance applicants are expected to understand. Students and volunteers then move to breakout rooms, where they work together in small groups to do exercises or practice answering the questions they may encounter on the test. Both the content of the lectures and many of the exercises that participants do in small groups are based on a standard curriculum issued by USCIS, to reflect the content of the naturalization exam.

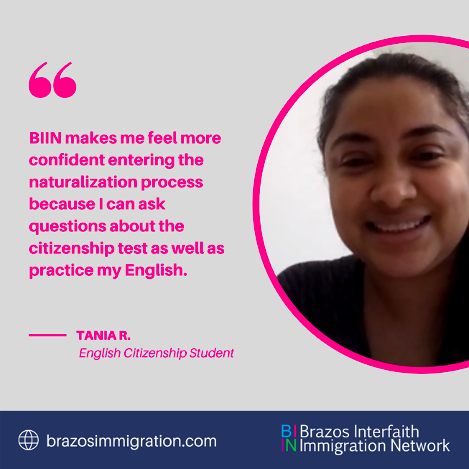

Jeremy Brett has helped teach the English citizenship classes since 2016, and currently serves as coordinator for the English section teachers. In his view, the relationships formed between students and volunteers are essential to the learning process. As he observed, “They meet one on one. They have conversations with each other, often about themselves or what they are learning. It’s a good way to connect with someone on a personal level and help them express themselves. Students appreciate the fact that volunteers are there to help them. As immigrants living in the U.S., they often face prejudice, but this [interaction] counters that a bit.”

The opportunity to work individually or in small groups with friendly volunteers is not only a powerful antidote to anti-immigrant sentiment encountered elsewhere. It also serves to increase engagement and confidence of prospective applicants who have heard about how hard the naturalization exam is or bring other fears to the process. As Jeremy notes, “Students arrive worried and unsure of the process. By the end, they understand it’s a workable process, it’s something they can do. They leave with a much greater sense of competence, that it’s something they have some control over.”

The welcoming attitude of teachers, volunteers and interns helps to put participants at ease. Geraldy Morua, a TAMU student, is one of two interns who worked with citizenship classes in spring 2021. In the course of the ten-week sequence, she witnessed steady change in the relationships between teachers, students and volunteers: “It went from formal greetings to casual stories about their pets and such. I saw how a comfortable and understanding relationship developed between students and volunteers. Students constantly ask questions about the lecture and activities done in class and the volunteers eagerly respond.”

Geraldy’s fellow intern, Niki Nguyen, observed a similar dynamic in the weekly sessions that she helped to manage: “I’ve noticed every single student engaging and interacting with teachers and volunteers. I’ve seen a steady increase in their engagement, as they stay laser-focused and retain information. The students show great enthusiasm when we are going over civics test questions and reviewing with flashcards. Rather than just showing up to class and listening, the students are actually interacting with teachers and volunteers.”

Student engagement in classes remains high, even though they have had to move from an in-person to an online format. TAMU student Madison Breeding served as a BIIN intern in the fall of 2020, working both with the English citizenship classes and the marketing team. She was so impressed by the energy of the citizenship classes that she returned this spring as a volunteer: “We have a lot of students who are friendly and happy to be there. They are excited to come into class, they are super animated. Zoom can be an intimidating platform, but it’s so admirable to see people come in and give it their all.”

Jeremy Brett likewise pointed out that by offering online classes, BIIN is able to reach some people who might not otherwise be able to participate: “One advantage of putting classes on Zoom is that more people can attend. For example, people with kids can more easily attend. I think attendance online is more consistent, or at least it’s up over what we saw in the last in-person classes.” While learning to use Zoom and being comfortable with its features can be challenging for some participants, it does not seem to have diminished in any way their desire to learn what they can from the program. As intern Geraldy Morua observed, “Some people are coming from work or taking care of their children during class. Some are in the middle of the citizenship application process, while others are just beginning to learn about it. They are hardworking, regardless of their circumstances, and they attend class ready to learn.”

Who participates in BIIN’s citizenship classes, and why?

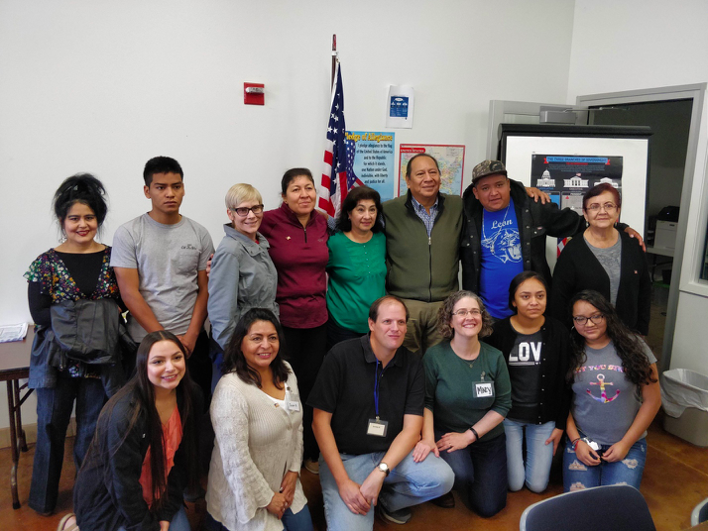

In order to apply for US citizenship via naturalization, people must meet certain residency and other eligibility requirements. In any given class, there will be people at different points in the process, people of different ages, linguistic and cultural backgrounds, and circumstances. What they share is their deep focus on a common goal: passing the naturalization exam and interview, and becoming a U.S. citizen. Thinking back to the many successive cohorts that he has worked with at BIIN in the past five years, Jeremy Brett had this to say: “We have students from many places. It’s amazing how people are so different in terms of their backgrounds, but when it comes to becoming a citizen, they have similar motivations. If you ask, ‘Why are you here — in the class?’ They have been here for decades, they love the country, and want to be part of the national life. They want to vote. Or they are doing it for their children.”

As a volunteer tutor, Madison Breeding has had the chance to get to know individual students and to better understand their motivations. She recalled the case of one student whose commitment to her family and to the U.S. particularly impressed her: “This woman is in the military, and she has a young daughter. She is seeking citizenship for her child and her family, but is also serving in the U.S. military [while she goes through the process]. I’ve been so impressed to see how dedicated she is. She wants to become a citizen so she can make things better for her daughter.”

Beyond the insights into the lives and perspective of people who are affirming their allegiance to the U.S. by becoming citizens, the experience of working with the program can help volunteers be more aware of their own role and responsibilities. As Madison explained it, “Many Americans [by birth] are really unaware of how the immigration process goes. But when you work with the naturalization test, and hear from a lawyer about how the interview goes, it helps you become a better US and global citizen. It’s a really rewarding program, even for people who are already citizens. It makes you feel more connected to the US.”

Many of BIIN’s long-time volunteers and supporters recognize that being involved with the citizenship program has additional rewards. It can be a way to strengthen the social fabric of our society as well as to uphold the fundamental principles of representative government in the United States. Jeremy Brett and Mary Campbell (former board president, and also a citizenship instructor) have invested a great deal of time and talent in this program, and have been recurring donors to the operating funds used to cover its costs. As Jeremy observed: “Through Mary’s and my involvement in BIIN, I’ve become more conscious of the issues and obstacles that immigrants face.. As someone who believes in the future of the U.S. as a multiracial democracy, I think it needs to have a thriving population of new citizens, of people who are able to vote and participate in democracy. They need to bring their dreams, desires, interests, beliefs, and consciences to the task. I’m ready to do anything I can to help make this process easier for them. It’s very rewarding, and I’m grateful that BIIN continues to offer this program.”

What can you do?

If you would like to support BIIN’s citizenship program as a donor or want to join this vibrant community in any capacity (as a participant, as a volunteer instructor, tutor or intern), there is room for you as well. Come see for yourself how rewarding it can be to deepen your knowledge, to grow in confidence, and to help welcome and support the future citizens who will help this country live up to its ideals. Join BIIN and our neighbors as we work together to build a diverse, democratic and inclusive society, one that recognizes and honors the dignity of every person, regardless of where they were born, who they love or what language they speak.