Carlos Espina is a familiar face to many who have been involved with BIIN. Since 2016, Carlos has found ways to share his time and talents with the organization and the community. Born in Uruguay but having lived and gone to school in the U.S. since the age of 5, Carlos is bilingual. As a senior at A&M Consolidated High School, he served as a volunteer in both the Spanish and the English citizenship classes at BIIN. After starting college at Vassar in Poughkeepsie, New York, Carlos volunteered with BIIN’s citizenship classes during the summer. In the summer of 2019, he also worked part-time as BIIN’s office coordinator.

In early March 2020, Carlos was again home on spring break, enjoying time with his family and starting to think about plans for the summer. As in the past, he was looking forward to running a soccer camp for local kids, a program called “Fútbol Para el Futuro.” But across the country, the situation was evolving rapidly, as COVID-19 spread and schools and businesses were shuttered. Soon the news came that Vassar, like other colleges, would be moving to online classes. Realizing that he would not be leaving town any time soon, Carlos approached BIIN with the proposal of offering a new cycle of citizenship classes online.

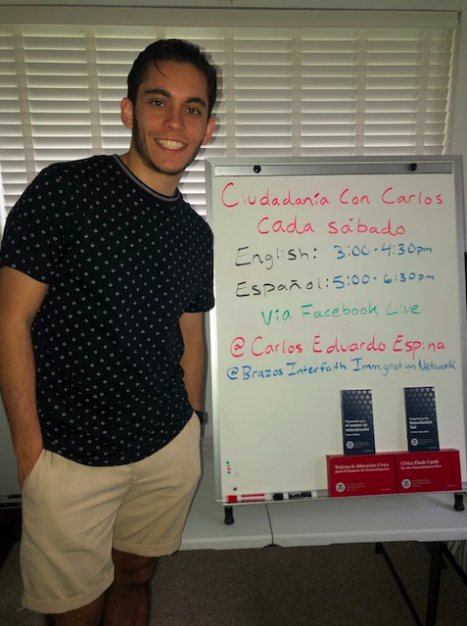

After talking with Program Coordinator Jaimi Washburn and Board Treasurer Rich Woodward (also a long-time instructor of citizenship classes), Carlos agreed that it made sense to use Facebook Live as the platform for distributing the online classes. Facebook is an outlet that many BIIN clients use and can easily access through mobile phones. Facebook Live made it possible to have some interaction with students but also to post the recorded session so that anyone who wanted to access the lesson at another time could do so. Carlos proposed to offer both an English and a Spanish language version of each weekly lesson, and started announcing the upcoming courses on Facebook and other social media.

Since March 28, Carlos has hosted two 90-minute citizenship classes on Facebook Live every Saturday afternoon. Familiar with the curriculum from his service as a volunteer, Carlos divided the topics — which cover the history of the U.S., the structure of its government and the responsibilities of citizens — into 8 segments. Early in the week, he takes time to go over the material, preparing notes for a short overview of that week’s topic. Using BIIN’s set of flashcards with questions that applicants can anticipate encountering at the naturalization exam, Carlos also pulls out the cards that are relevant to each week’s topic. He prepares a document that provides a summary of the material covered in each lesson along with related digital resources, so that students have ways to follow up and do more self-study. While preparing for the week’s classes, Carlos also posts a couple of reminders on Facebook, so that students remember to log on.

Saturday afternoon comes. Carlos shuts himself in his bedroom, where he has a whiteboard on an easel, an open laptop, and his cellphone set up on a tripod. After greeting his audience, he launches into a short lecture, introducing the topic of the week and laying out key points. This is the part that requires the most preparation, as he wants it to be engaging and fluid. Because the lecture is recorded and posted on Facebook Live, he knows he will not be interrupted with questions or comments, as he would be in a face-to-face setting. But he doesn’t want to ramble or lose his audience, and so having organized points and clear transitions mapped out in advance is crucial.

After 20 minutes or so, Carlos switches to the more interactive part of the lesson. He asks a question from a flashcard, and then pauses so that students have time to answer it, either to themselves or by typing an answer using the chat function, where Carlos and anyone logged in can see it on the screen. After allowing time for several participants to answer, Carlos confirms the correct answer and clarifies any misunderstandings. The lesson proceeds in this way until the class has worked through all of the relevant questions. Students can also use the chat function to ask questions of clarification.

From the perspective of the instructor, Carlos admits, it’s an imperfect method. On his screen, he can see the number of people who are logged in. And as they answer questions with the chat function, he can see individual names and start to recognize who is engaged. But he cannot scan the room, read students’ body language, or encourage someone who has been quiet to speak up. He has no way to compel all students to answer, or to know if someone did not answer because they were confused or because they turned to engage with a needy child at home. “With limited feedback,” observes Carlos, “it’s hard to measure the progress of your students.” Nonetheless, students show up, week after week, sometimes as many as 30 – 50 for a class session. And from the enthusiastic remarks and thanks posted in the comments section, it’s clear that his efforts to connect with students and to make the naturalization questions feel familiar and within their reach are appreciated.

At the end of the session, Carlos recaps the topics covered, reminds the students of ways to remember things that some found hard, and promises to send a PDF of resources for self-study to those who have provided contact info. He misses the easy give and take of classes taught in person, and looks forward to the day when BIIN can safely resume its face to face gatherings.

But Carlos points out that the options developed during the pandemic may also change the way BIIN and other organizations choose to operate in the future. In particular, there may be room for “hybrid” offerings: classes or workshops that meet in person, but are recorded and posted online, so that interested people who cannot easily attend (due to health, work, family responsibilities, etc.) can still take advantage of these opportunities. By diversifying the ways that people can access BIIN’s programs, we can continue to work to improve the lives of all of our neighbors.

Through his energetic and committed example, Carlos Espina has shown not only that it’s possible to make these changes, but also that we can harness the power of digital technologies without turning our backs on the essential task of building community. Thank you, Carlos, for continuing to be so generous with your time and talents!