BIINtern Sequels: José Morales, humanitarian aid

In the summer of 2019, José Morales was half way through his junior year at Texas A&M. A sociology major from Victoria, Mexico, he knew he wanted to do work that would help people: maybe something related to economic development or humanitarian aid, possibly with a nonprofit organization. But he wasn’t sure what specific skills that would require, or how to get there. He spoke with Dr. Katheryn Dietrich, a sociology professor who offers a class to help TAMU undergraduates learn through internships in the local community. Hearing about his interests, Dr. Dietrich suggested that José apply to serve as an intern with BIIN.

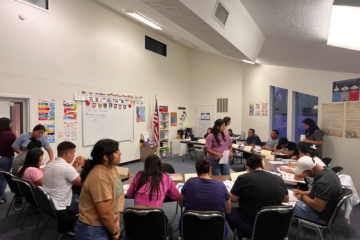

José still remembers his first conversation with BIIN Director, Jaimi Washburn: “It was my interview for the internship, and I was so nervous going into it… But Jaimi had such a great attitude! She put me at ease right away.” By the end of the conversation, both José and Jaimi knew that a good match had been made. In fall 2019, José served as an unpaid office and volunteer intern. In this role, he did many things: he answered phones, received office visitors and communicated with IRA volunteers about requests for assistance; helped track volunteer assignments and hours; created volunteer job descriptions; conducted a volunteer survey; reorganized the office and made it more functional. José says that from the beginning, he enjoyed the culture of teamwork at BIIN, the sense that everyone’s contributions were valued, whether they were interns or staff. Jaimi, in turn, appreciated José’s “work ethic, problem-solving skills and the positive energy he brings to the team.” As Jaimi put it, “He builds trust quickly and manages personal and professional relationships with sensitivity and positivity.”

Impressed with his skills, Jaimi invited José to move into a part-time paid position as office and volunteer coordinator, starting in January 2020. Along with Adriana Stowe, José was one of the first former interns to take on a part-time paid role at BIIN. As office and volunteer coordinator, José was responsible for managing BIIN’s volunteer program which included supervising one of the spring 2020 interns, managing the volunteer database with approximately 450 volunteers, recruiting and scheduling volunteers, creating a user’s manual for the Volgistics system, managing the volunteer appreciation program, and assisting with various office projects.

In the spring of 2020, BIIN had a record number of interns serving in different roles, as well as another new part-time staff member, Janet Morford, who was hired in February 2020 to help supervise interns and enrich BIIN’s communications and development efforts. The shared one-room office was a busy place, and having more than one staffer who could ensure a friendly and competent presence during office hours was valuable.

In March 2020, as the coronavirus pandemic spread and BIIN’s operations went remote, everyone was required to pivot. In this context, José continued to be a tremendous asset to BIIN. He took responsibility for checking the office phone remotely and relaying messages (many from community members seeking help). With other staff and interns, he helped to collect, curate, translate, and disseminate up to date information about community resources to meet basic needs (for food, medical care, rent/utilities assistance, etc.). Along with staff, board and key volunteers, he helped create and keep records for the BIIN CARES Fund. José also helped figure out the logistics of moving operations and programs online.

By fall 2020, BIIN’s citizenship and English classes were fully operational online, and the IRA team began offering monthly “drive-up” clinics in the parking lot, in addition to responding to inquiries via phone and email. José, by then in his final semester at TAMU, continued to work part-time for BIIN, while also attending classes and working with an interdisciplinary research team led by Professor Samuel Cohn. With BIIN’s signature programs operating online or remotely, it became all the more important to have people with good digital skills to help connect with clients and provide support for program leaders and other volunteers working in new ways. José’s calm demeanor, his bilingualism, his ability to work independently and to lead others through new routines were invaluable.

After his graduation in December 2020, José returned to his family’s home in Houston, and continued to look for full-time employment, preferably related to economic development or humanitarian aid. This was not an easy time to look for a job or start a new chapter, as so much was still on hold or at risk due to the pandemic. But José persisted, and his efforts paid off: In March 2021, he began working with Catholic Charities as assistant lead case manager at St. Michael’s Home for Children, in Houston. According to José, “BIIN is what got me this job!”

Having worked with a small nonprofit where staff members knew him well and could speak to his skills in letters of recommendation and conversations with potential employers was helpful. Along with what he had learned through classes and research at TAMU, José felt his work with BIIN had really opened his eyes to the specific needs of immigrants and refugees, and made him comfortable in the nonprofit world.

Having worked with a small nonprofit where staff members knew him well and could speak to his skills in letters of recommendation and conversations with potential employers was helpful. Along with what he had learned through classes and research at TAMU, José felt his work with BIIN had really opened his eyes to the specific needs of immigrants and refugees, and made him comfortable in the nonprofit world.

José Morales was willing to talk with us about this new chapter in his life, but wanted to make it clear that the views and opinions he expresses here are his alone and do not necessarily reflect the position of Catholic Charities.

St. Michael’s Home receives and supports immigrant children who enter the U.S. as unaccompanied minors, that is to say, without an adult, after they are released by the Department of Homeland Security to the Office of Refugee Resettlement. A licensed facility under contract with the ORR, St. Michael’s houses, clothes, feeds, provides medical care, educates and works with these young people until they can be safely reunited with relatives or other sponsors in the U.S. As is the case with many shelters across the country, many of the youth that St. Michael’s Home works with have come from the so-called “Northern Triangle” — Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador – or from poor communities in other parts of Latin America and the Caribbean, including Mexico, Venezuela, or Haiti. Many come to the U.S. with the intention of joining a family member, but some arrive without any known contact, simply in hopes of being able to make a better life for themselves.

Migrant children wait to be processed at the U.S. southern border. U.S. law requires that they be detained no more than 72 hours before being sent to shelters for minors, overseen by the Office of Refugee Resettlement, an agency of the Department of Health and Human Services. Photo: Adrees Latif/ Reuters.

As part of the case management team at St. Michael’s, José works on setting up and verifying the safety of the reunification plan for individual minors. “We work with the Office of Refugee Resettlement and other federal agencies to find a safe placement for them, whether it’s with a family member or if that’s not possible, in long-term foster care,” he explains. Although José frequently interacts with the kids themselves, much of his day involves working with his colleagues: supervising the team, helping set up the services and support that the youth will need to receive when they leave St. Michael’s, and making sure they are complying with government policy in regard to every aspect of proposed placements. Many minors are deeply traumatized by violence or ruptures experienced in their country of origin, as well as by the dangers and dislocations of their migration to the U.S. At this point in their lives, they need caring and competent adults who will do their best to see that they go on to live in circumstances where they can heal and thrive.

Case management is demanding work, and to work effectively with an extremely vulnerable population like these young refugees requires many skills. José points out that the skills he uses every day in his work at St. Michael’s include several that he acquired and honed in his work with BIIN: working with a team, helping to build a culture of teamwork by developing relationships, recognizing others’ contributions, and creating clear guidelines and resources that everyone can use. “That goal-oriented way we had of working at BIIN,” says José, “I learned it from Jaimi. And I brought it with me to Catholic Charities. I have worked to help my team here identify and focus on specific goals.” He also sees parallels in the ways that both nonprofits use systems to track cases as individuals move through long complex processes. The hours he spent at BIIN working to update records and streamline procedures helped him know how to use these tools to the benefit of the team.

Having worked with Catholic Charities for a little over a year now, José has learned many things not just about the young people who come to St. Michael’s Home but also about the wider phenomenon of mass migration of unaccompanied refugee children. There are several things that he would like for others to know about the situations of unaccompanied minor migrants in the U.S.

“The vast majority of these kids are coming from very precarious situations,” explains José. “They are coming from deep poverty. Some have been abused, or face trafficking, or threats from criminal gangs… But most of all, it’s poverty, and they are trying to find a better future.” Through social media, impoverished youth see images of life in the U.S. and they too want to live in safety, with material comforts, and opportunity. Faced with endless poverty and specific dangers in their country of origin, and seeing these glimpses of how people live in the U.S., many youth feel that their only real option is to leave their homes and try to make it to the southern U.S. border.

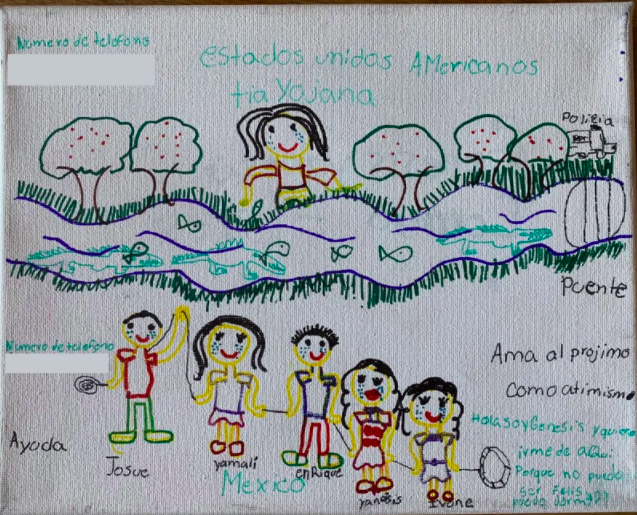

What lies across the border, as seen by a child forced to remain in Mexico.

Young migrants travel on the top of a train known as “La Bestia.” Photo by Nick Oza/The Republic.

Having no means to do otherwise, they take enormous risks as they travel. As José puts it, “They come walking, they come in buses, on top of trains, in trucks. They come alone, they join groups of people they don’t know. They make these very dangerous trips, to get to the border, to be here – all in order to have a better life. And we have to try to be compassionate about that.”

In other words, people who live in the U.S. need to understand the push and pull factors driving mass migration, and have empathy for all that unaccompanied minors and other migrants go through, just to have a chance at a better life. For anyone interested in learning more about the motivations and lived experience of unaccompanied minors, José strongly recommends a report by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), called Children on the Run.

José emphasizes that even after unaccompanied minors enter the U.S., they are still vulnerable to exploitation. Catholic Charities works with partner organizations such as the U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants and the Young Center for Immigrant Children’s Rights. Together, they try to make sure that the youth will be safe and that their needs as minors will be respected, before they are released to family or other sponsors. As José explains, “There is a lot of human trafficking, labor trafficking, things like that you have to watch out for. That’s a big deal for us. We do a lot of assessments [of potential placements] to make sure these kids are not victims of labor trafficking. They are coming to live with a family member, but they can’t work, they have to go to school.”

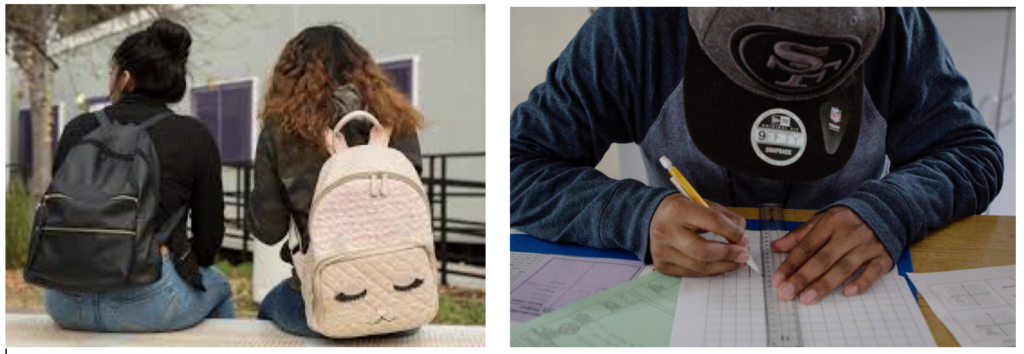

Public schools in the U.S. sometimes offer special programs for migrant youth. Photos by Anne Wernikoff.

Ensuring that migrant youth attend school can be a challenge for many reasons, including the fact that many of them have other hopes for their future. As José observes, “The main idea that a lot of the kids have when they come to the US is, ‘I’m going to work, I’m going to be able to make money, I’m going to help my family in my country of origin.’ School is not Plan A for most of them. But it’s a requirement because they are minors, and it’s part of the requirement for a person that agrees to sponsor or take care of them: they will go to school.” Thus, the role of the case management team at St. Michael’s Home, just as in many other shelters working with unaccompanied minors, is to try to ensure their safety, while also helping these young people understand the laws and policies that they and their sponsors are expected to abide by in the U.S. José and his colleagues serve as advocates for the kids during their brief time at St. Michael’s, trying to make sure that they are safe and will have the conditions to heal and grow, wherever they end up.

Working with this very vulnerable population has been both eye-opening and rewarding for José. Thinking about what he has learned from his work at St. Michael’s, he admitted, “It has been hard at times, especially compared to the worry-free times I had as a student. When you are working, you start to see hard situations like those that exist for the kids we serve. It can be tough, but it is also very fulfilling, especially when you realize that these kids now face a brighter future, simply by being in the U.S. They came here with big dreams and hopes, and knowing that we helped them be a little closer to realizing those dreams is a great feeling.”

“Aqui y Alla,” artwork by Freddy Argulla, a young migrant from Mexico who came to the U.S. as an unaccompanied minor.

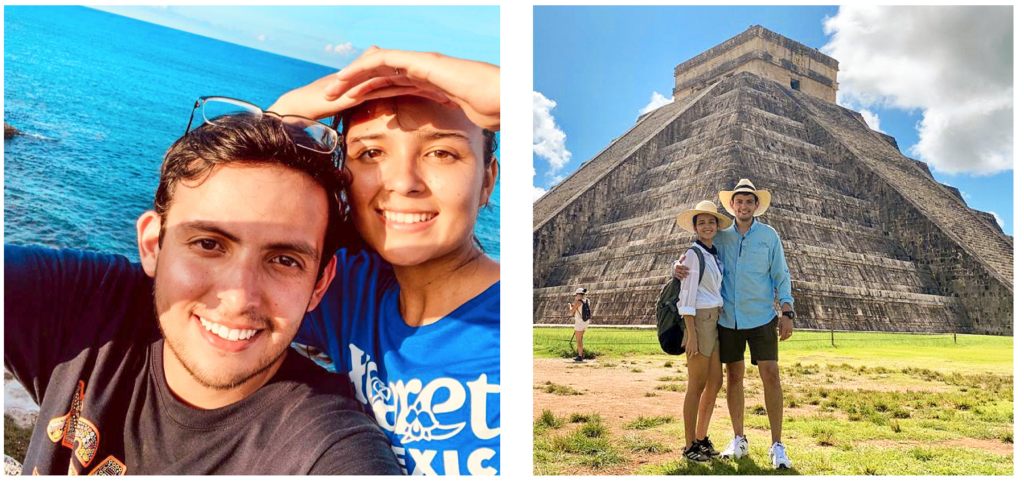

Beyond all the time and energy José puts into his work with Catholic Charities, he has also been investing in other parts of his life as a young adult. In October 2021, he and Anna Noriega were married and set up a new home together. The newlyweds have enjoyed the chance to do some traveling together as public health conditions have improved. Ever eager to use his skills as a researcher, José has also continued to work with the interdisciplinary team led by Professor Samuel Cohn that he joined while at TAMU. Working on issues of poverty and economic development, the team has written a paper that José will help to present at an upcoming conference in Barcelona. Given his deep interests in understanding mass migration, its causes and impacts, José is planning to get a graduate degree in international development before long.

Looking back, and looking at where he is now, what advice would José give to his younger self or to other students who are trying to find their path? Ever thoughtful, José paused for minute, before sharing these tips: “I think it helps to realize that we as human beings have to be constantly growing, not just professionally, but also mentally, spiritually. Whatever you do, do it with passion, and know that serving others is very fulfilling.”

Thank you, José, for all that you have given and done, to support the work of BIIN, to advocate for the safety and interests of unaccompanied minors, and to help us better understand the factors that make mass migration such a complex and compelling issue. Wherever you go, whatever you do, we know you will do it with great skill, genuine passion and deep compassion for your fellow human beings. Best wishes from all of us at Team BIIN!